Warning: Spoilers below

Now that Stranger Things has concluded its nearly decade-long saga of teenage grit, government monsters, and storylines inspired by the CIA conducting secret and unethical experiments on Americans, I—like many other viewers—have questions. (If you haven’t watched Season 5, this is where you should stop reading.)

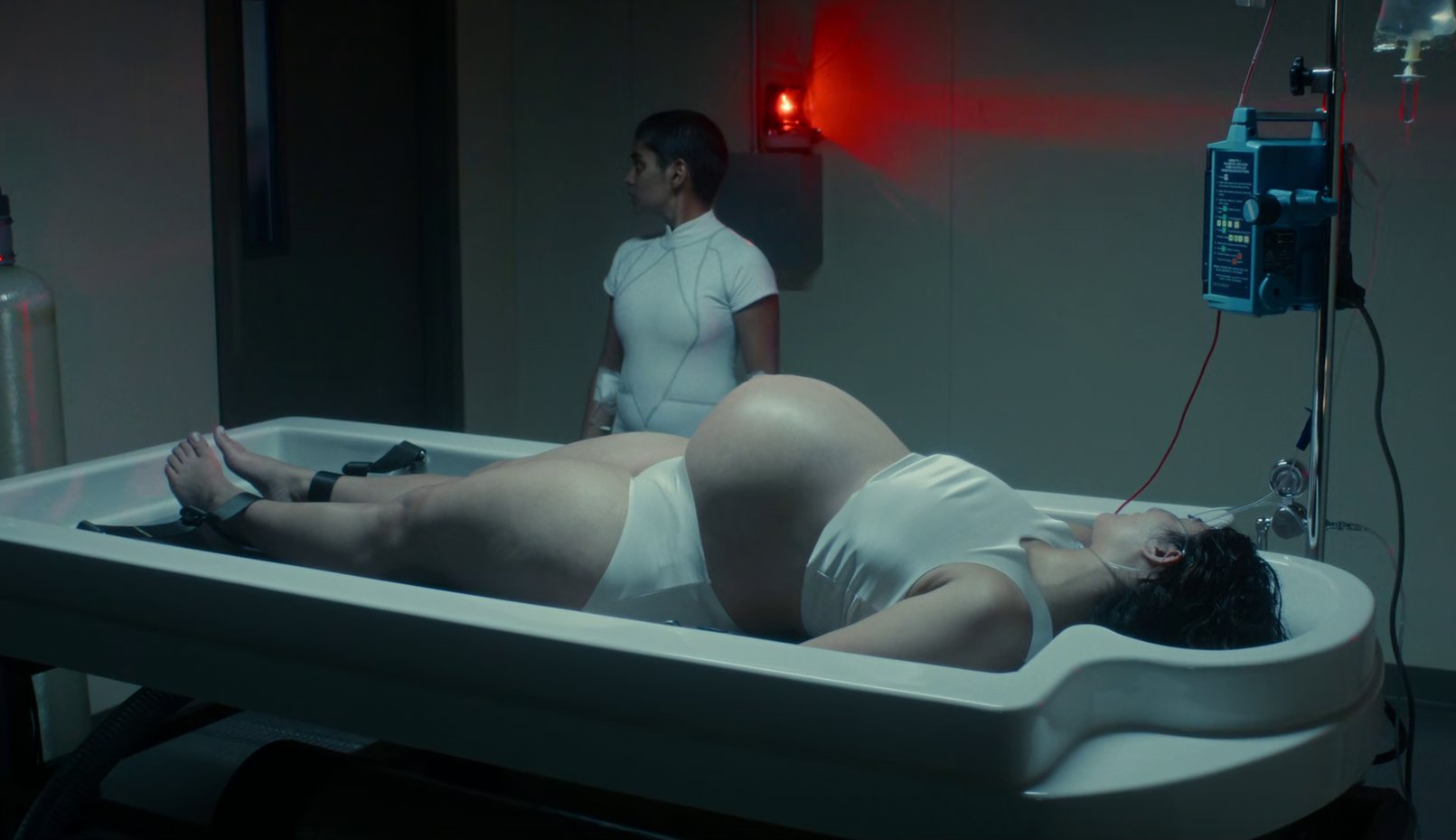

Is Eleven dead or alive? What was that magical little lava rock thing that made Vecna the villain he is? Did Robin Buckley ever go public with her girlfriend, Vickie Dunne? And whatever happened to the assembly line of pregnant women being injected with magical superpower blood?

Stranger Things is obviously science fiction, but Eleven’s backstory—in which she was born with psychokinetic and telepathic abilities because her mom participated in MKUltra, a covert CIA operation to develop mind-control techniques during the Cold War—was partly inspired by actual covert CIA operations from the 20th century, one of which was literally called MKUltra.

Eleven has other numbered “siblings,” including Eight, who has the powers of illusion and reveals in Episode 5 that she was recaptured by the government and extracted for her “special blood.” But that blood, she eventually learns, was being injected into pregnant women she found lined up in hospital beds—in what she later assumes to be a revival of MKUltra.

But fictional monsters and dimensions aside, the U.S. has a long history of exploiting women’s bodies (often impoverished, Black, or disabled women) at the cost of scientific development. And at least one medical experiment from the 1940s mirrors this macabre storyline.

Between 1945 and 1949, hundreds of pregnant women who sought free care at a prenatal clinic at Vanderbilt University were given what they were told were vitamin drinks when, in reality, the drinks were iron solutions laced with radioactive isotopes. Researchers wanted to study iron absorption during pregnancy, and the radioactive iron would allow them to track the chemical element in pregnant bodies. The study was partly funded by the Public Health Service (which, at the time, was the primary federal health agency) and was conducted in coordination with the Tennessee Department of Health. Internal documents indicate the research primarily targeted white women.

The radiation exposure—absorbed by both the women and their fetuses—was roughly 30 times higher than natural background levels. A follow-up study published in 1969 concluded that at least three of the children likely died as a result of the exposure.

This only came to light in the 1990s, when then-Secretary of Energy Hazel O’Leary admitted her department—and the Atomic Energy Commission that came before it—may have conducted radiation studies on Americans without their consent. Years earlier, in 1986, a congressional committee quietly published a report called “American Nuclear Guinea Pigs: Three Decades of Radiation Experiments on US Citizens” that chronologically listed such experiments, but was largely ignored by the press.

One of the participants in the Vanderbilt program, Emma Craft, spoke to the Independent in 1994 about her daughter, Carolyn, in 1956—almost certainly a result of being a radioactive “guinea pig.” Emma revealed that when her daughter died, she weighed only 40 pounds and her face was disfigured by cancerous lumps. (According to the CDC, prenatal radiation exposure can put the fetus at risk of growth restriction, malformations, impaired brain function, and cancer.)

In 1993, the Department of Energy estimated that 751 people were given the radioactive pills, and a lawsuit was filed a year later on behalf of 800 people against the university, seeking damages for illness, death, and emotional distress, as well as access to medical records. To this day, Vanderbilt officials say they’re unsure if the women were told of the possible effects of radiation, or if they even knew they were being given the pills.

Craft said she had no idea.

In an effort to expose more of the federal government’s widespread postwar radiation experimentation, in 1994, the Clinton administration assembled an investigation panel and launched an “human experimentation hot line.” It received more than 500 calls in the first hour.

What followed was a catalogue of abuse. In a young boys’ school for mentally disabled children in Massachusetts, dozens of young boys were fed milky Quaker Oats laced with radioactive tracers. In an Oregon penitentiary, dozens of inmates had their testes deliberately exposed to radiation to examine whether it would impact reproductivity. (They were not informed of the risks, and at least eight men had children with genetic defects afterwards.) And in New York, as part of the Manhattan Project, at least 31 patients at the University of Rochester medical center were given radioactive plutonium, uranium, polonium, americium, or zirconium—all of whom died by 1995.

The Energy Department, of course, was just the tip of the iceberg—other agencies, such as the Department of Defense and NASA, had helped fund close to 4,000 secret studies on people without their knowledge or consent.

Speaking from the White House in 1995, Clinton apologized to a handful of survivors. “When the government does wrong, we have a moral responsibility to admit it. A sitting U.S. president acknowledging government wrongdoing and apologizing to its victims? Talk about science fiction.

Clinton also vowed to create a bioethics advisory panel to regulate research and compensate victims. But while the panel estimated tens of thousands of subjects were unknowingly tested on, it wasn’t able to identify most of them. “Of the 10,000 calls we received, about 3,000 individuals gave us enough information to enable us to look in records and, in all the searching of a quarter of a million pages, we found only 50 names,” O’Leary explained.

The Duffer Brothers—the directors and creators of Stranger Things—haven’t explicitly said if the show’s pregnant person plotline was loosely based on any clandestine government operations. But, according to them, the pregnant women were all killed when Eleven destroyed the Upside Down. Speaking to ScreenRant, Matt Duffer explained Eleven’s choice as “courageous and selfless.” “All those pregnant women died because that blood did not work. But if that were to work, then you’ve got dozens of children who are going to grow up just like her and that are going to be turned into weapons and abused,” he said. “So that was sort of where we landed.”

We never see the government operatives who tried to revive MKUltra face any kind of consequence for experimenting on pregnant people—giving the science fiction series a disturbingly nonfiction ending.

Like what you just read? You’ve got great taste. Subscribe to Jezebel, and for $5 a month or $50 a year, you’ll get access to a bunch of subscriber benefits, including getting to read the next article (and all the ones after that) ad-free. Plus, you’ll be supporting independent journalism—which, can you even imagine not supporting independent journalism in times like these? Yikes.