Over the span of a single lifetime, the world has changed in ways that would have been virtually unimaginable in the first half of the 20th century. Two major breakthroughs that occurred in physics — relativity and quantum physics — suddenly made a number of previously unthinkable endeavors possible. From modern electronics to computers, smart phones, the internet, brain imaging and more, everyday life in 2021 is vastly different from what it was back when many of us were first born.

One of those technologies that’s been revolutionary for our society is GPS: the Global Positioning System. From anywhere in the world, signals can be transmitted by a network of medium-Earth orbit satellites to wherever your location is, pinpointing your position to an accuracy of better than 1 meter (3 feet) more than 95% of the time. Devices with the latest (L5) receivers, beginning in 2018, are now capable of reliably determining your location to within 30 centimeters (12 inches).

Unbeknownst to most people, however, the science underlying this technology was primarily developed by two people: Albert Einstein, whose theories of special and general relativity both play an important role, and Gladys West, a humble and largely-unheralded black woman who passed away at the age of 95 on January 17, 2026. Her scientific contributions enabled us to understand geodesy and the shape of the Earth well enough to make GPS technology possible. While many others played a role in designing, deploying, manufacturing, and operating the satellite array that powers GPS, none of it would have been possible without West’s key insights. Here’s the science behind why this “hidden figure” of GPS is invaluable.

Here on Earth, GPS is truly a technology that’s only been possible since the dawn of the space age. At its core, GPS is enabled by a network of satellites that each carries an accurate record of its position in space and the passage of time on board, with the latter enabled by atomic clocks: one aboard each satellite. Those satellites continuously transmit their position and time data through a radio signal to receivers located anywhere on Earth.

Since the speed of those radio waves — the speed of light — is a constant, anyone who receives a signal from any four GPS satellites at once, with known timestamps and position stamps, can determine their three-dimensional position in space and their “position” in time (i.e., your “clock deviation” from the time on board the satellites).

At an orbital height of 21,180 kilometers (12,540 miles), a little more than three times the radius of the Earth, only 24 satellites are required to provide full coverage to the entire Earth at once. While other nations, such as Russia and China, have their own GPS-like systems in place, it’s the United States’ GPS system, consisting of 31 operational satellites at last count, that freely serves the entire world.

Physically, however, you have to know three very important things in order to translate those received signals — the radio waves arriving from the various GPS satellites — into both a precise and accurate position and time. Those things are:

- motion, which includes the motion of the satellites through space and the motion of you, the receiver, on Earth’s surface, since objects in motion experience time dilation and length contraction under the laws of special relativity,

- curved space, which includes the gravitational blueshifting and gravitational time dilation of light as it moves from a region of lower spatial curvature (in space) to a region of larger spatial curvature (on Earth’s surface), following the rules of general relativity,

- and the effects of Earth’s gravity, which vary by small but substantial amounts over the Earth’s surface, owing to effects such as mountains and valleys, the varying thickness of Earth’s crust, and even the amount of subsurface water (which changes over time) present at various locations in the soil.

Only by including the effects of special relativity, general relativity, and the variations in gravity across Earth’s surface (also known as the science of geodesy) can precise, accurate positioning be calculated from the data acquired by various GPS satellites.

Credit: Vladi/Wikimedia Commons

It’s important to remember why relativity — both the special and general versions — are so important. Up in space, these satellites orbit Earth at significant speeds: 13,900 kilometers-per-hour (8,600 mph). Meanwhile, anyone on the surface of the Earth is experiencing the effects of Earth’s rotation, which range from about 1,670 km/hr (1,040 mph) at the equator down to zero at the north or south poles, in a latitude-dependent fashion. Even though these relative speeds are very slow compared to the speed of light, even a small omission, like a miscalculation in the signal’s arrival time of a single microsecond, can lead to an error in your calculated position by the size of a football stadium!

Similarly, the curvature of space itself is smaller the farther away you get from a large mass, and being more than 20,000 kilometers up above the ground puts you in a significantly weaker gravitational field than someone on Earth’s surface. Time passes at different rates in stronger or weaker gravitational fields, and the amount of that time difference needs to be taken into account. Without these corrections due to general relativity, every GPS measurement of your position would be off by about 30 meters (100 feet) — not uniformly but rather in an inconsistent fashion — as the various GPS satellites continued to orbit the Earth.

Fortunately, the rules of relativity, as put forth by Einstein in the early 20th century, are completely sufficient for taking care of these two effects.

Credit: NASA/Karen Nyberg

However, there’s another piece of information that we need to fold into the equation: the fact that Earth isn’t a uniform, perfect sphere, with the same exact gravitational properties everywhere. In fact, when you get down to accurate enough precisions, the gravitational acceleration at Earth’s surface — even though it always points in the same direction (toward the center of the Earth) — can differ by amounts approaching a full percent. That might not seem like all that much, as it means that the gravitational acceleration on Earth is uniform to the 99% or more level. Still, those small relative differences lead to enormous absolute errors when you translate that into positions on Earth, which makes accounting for those differences both precisely and accurately all-important!

If you took a high school level physics class, you might be used to approximating the gravitational acceleration from every point on Earth’s surface as 9.8 m/s² (32 ft/s²), which is good enough to solve many problems in physics. However, there are many factors that lead to deviations from that value at any particular location.

- The Earth is flattened at the poles and bulges at the equator, due to our planet’s rotation about its axis, leading to greater gravitational acceleration at the poles (which are closer to the Earth’s center) and smaller ones at equatorial latitudes.

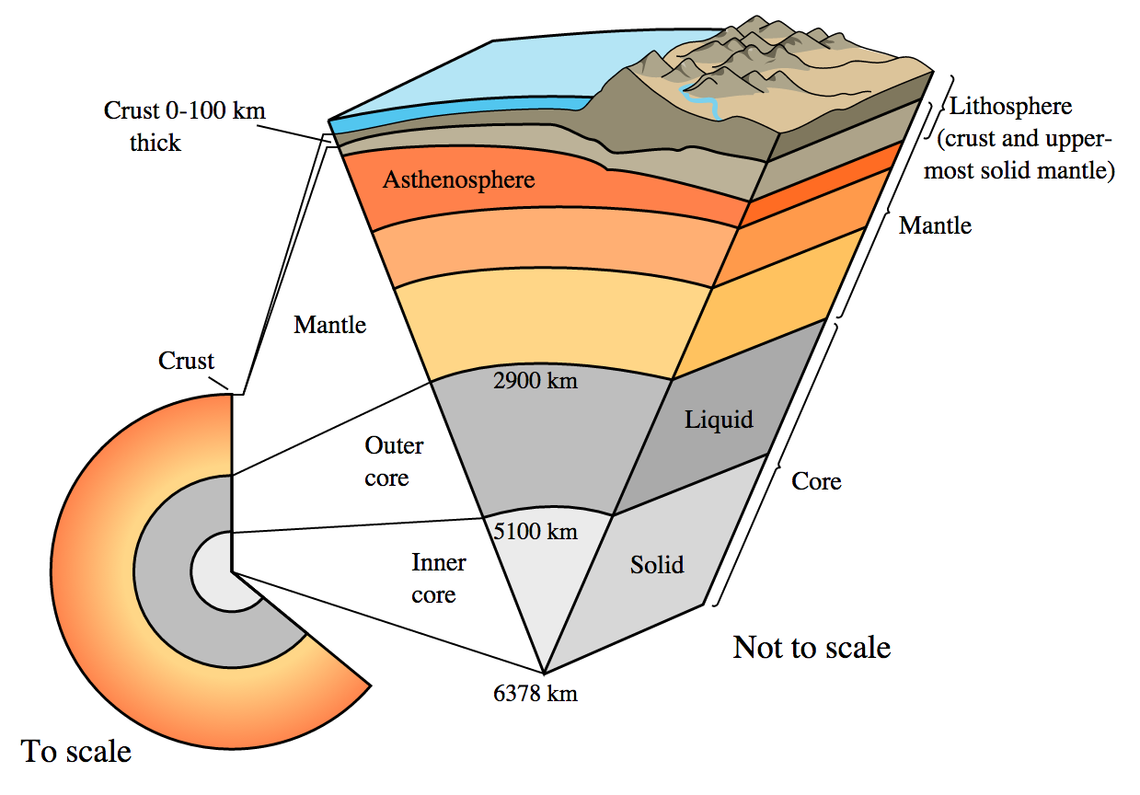

- The Earth has mountains, valleys, deep oceans, and trenches, causing the crust to vary in thickness from as little as 5 km on the ocean bottoms to as much as 45 km beneath the heaviest mountain ranges, where the crust is the least dense (i.e., least massive per-unit-volume) component of Earth’s interior.

- And there are continuously occurring changes due to features like ice forming and melting, water retention and depletion in the ground, and even major weather events.

All told, the actual acceleration on Earth’s surface can be experimentally determined to be as little as 9.764 m/s² and as great as 9.834 m/s²: corresponding to a difference of 0.7% between those two extremes.

Credit: USGS

If we need to precisely know the gravitational properties of any place a receiver might be who wants to precisely determine their location with GPS, we need to map out — continuously and in real-time — the gravitational field of the Earth at its surface. The way we can accomplish this, again, only possible since the dawn of the space age, is with satellite geodesy.

Ever since the first artificial satellites were launched, beginning with Sputnik way back in 1957, we’ve noticed that you can’t simply approximate the Earth as a “point mass,” where you idealize it as though all of its mass was concentrated at its center. This was an approximation first used by Newton: going all the way back to the birth of the notion of gravitation itself. However, simply by tracking satellites in motion around Earth, we began noticing tiny deviations that occurred in their:

- speeds,

- positions,

- and the amount of time it takes to complete a full revolution around Earth.

These deviations provide us with information about the departure of Earth from being a perfect, uniform sphere, and those departures explain why it’s incorrect to approximate Earth as a point mass.

The earliest satellites in the 1950s and 1960s taught us by how much the Earth was flattened due to its rotation; today we have permanent geodetic networks and accurate measurements of not only Earth’s gravitational field at every point, but how that gravitational field changes on timescales as short as a few days. When droughts, floods or wildfires occur, the changes in the gravitational field due to mass loss or increase can actually be measured in near-real-time.

In order to make these measurements accurately, we need to have a very good understanding of altimetry, which includes both the height of the ground above sea level and also the height of any orbiting satellite above the Earth’s surface. Because of the fact that Earth’s oceans are so massive, and also that the ocean height changes with time due to tides and other, transient effects — again including ice melt, ocean temperatures (water is densest at 4 °C and takes up more volume at either higher or lower temperatures) — remote sensing of Earth’s oceans is also vital to this endeavor. Only by determining how the mass of Earth itself is distributed, including at and beneath the surface, can we map out its gravity field in a precise, accurate way.

Today, we have many satellites and multiple techniques all working together to take unprecedented measurements of the Earth and its gravitational properties. Our global navigation satellite systems, with GPS the most prominent among them, absolutely rely on our knowledge of these properties all around the Earth.

Credit: C. Reigber, Journal of Geodynamics, 2005

With a full, global map of our planet’s gravitational properties, we can construct something known as the Earth’s geoid: the shape that the oceans would take if they were extended through the continents and if the tides and winds were absent, giving a purely gravitational map of our planet through an irregular surface.

In order to enable all of this, a number of advances needed to occur: advances that were not in place at the start of the space age. We had to:

- Construct mathematical models of the shape of the Earth, enabling us to understand how various points on our planet experienced gravity differently from one another.

- Develop methods for measuring altitude and translating those measurements into actual, accurate values for distance.

- Conduct radar altimetry to remotely sense Earth’s oceans, and again, translate that data into accurate values for altitude and distance.

Even with those advances, bringing them all together to model the gravitational influence of the Earth at-and-above every point on the Earth remained an additional challenge. It was only with the advent of sufficient computing power that we could deliver increasingly precise models of Earth’s geoid, finally enabling a global navigational satellite system that could accurately determine your position anywhere on Earth.

Although it took a large team of many people to accomplish this, perhaps the most instrumental single person in bringing all of this to fruition was Gladys West: the second black woman ever hired (way back in 1956) at the Naval Proving Ground in Virginia. Here’s why her big contribution to GPS is worth remembering.

Originally a computer programmer, West specialized in large-scale computer systems and data-processing systems for the analysis of information obtained from satellites. She was the very first person to put together altimeter models of Earth’s shape to significant precision in the 1960s, and served as the project manager for Seasat: the first satellite to perform remote sensing of Earth’s oceans. She was recommended for a commendation for her work, as she worked extra hours to optimize her team’s processing algorithms; as a result of what she did, she cut the processing time for these remote sensing applications in half.

If this were all she had done, it would be work worthy of recognition even now, decades later, as pioneering and foundational in the field of geodesy. But she accomplished far more than even all of that. Perhaps her most revolutionary work occurred around 45 years ago, as she herself wrote the computer program that calculated Earth’s geoid to sufficiently high precisions and accuracies — for the very first time — to enable the existence of a useful GPS system. This is no small feat; to accomplish this, one has to account for variations in all the forces and effects that can distort the shape of the Earth.

Then, building upon that, she literally wrote the guide for the next generation of radar altimeter satellites, teaching others how to increase the precision of satellite geodesy when improved technology finally arrived. That’s another key aspect to her work worth remembering: a forward-thinking improvement to what was possible in her own time that would help the next generation accomplish what she could only envision at the time. After retiring from the Naval Surface Warfare Center (which the Naval Proving Ground evolved into) in 1998, she went back to school and completed a PhD. She was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame in 2018.

It’s pretty rare to be able to mention another person’s name in the same breath as Albert Einstein unironically, but when it comes to the science of GPS, there is no one else, besides perhaps Einstein, whose contributions were more significant than Gladys West. In an interview conducted with her in 2018, she let slip a fascinating detail about her own life: despite the ubiquity of GPS and her role in developing it, West still prefers to use a paper map when she travels.

When she was inducted into the Air Force Hall of Fame, Air Force Space Command recognized her as one of the hidden figures who performed vital computations for the United States military before the era of electronic systems. Praising her work, commanding officer Captain Godfrey Weekes lauded her as follows:

“She rose through the ranks, worked on the satellite geodesy, and contributed to the accuracy of GPS and the measurement of satellite data. As Gladys West started her career as a mathematician at Dahlgren in 1956, she likely had no idea that her work would impact the world for decades to come.”

Her life’s work is a testament to the promise of science: you work hard, you develop skills and hone your talents, you apply what you’ve learned to a real problem involving cutting-edge (and even future) data, and you enable the development of technologies that can improve the lives of all. Rest in power, Gladys West; may the world remember you every time we reliably use the GPS system you developed to show us precisely where we are.

An earlier version of this article was first published in February of 2021. It was updated in January of 2026.

This article Remembering Gladys West: who used Einstein to create GPS is featured on Big Think.