Starting on the night of January 19, 2026, planet Earth was treated to a global show that had only been seen once before in the 21st century: a spectacular auroral display that wasn’t triggered by a solar flare or by a coronal mass ejection, but instead by a completely different form of space weather known as a solar radiation storm. Whereas solar flares normally involve the ejection of plasma from the Sun’s photosphere and coronal mass ejections typically involve accelerated plasma particles from the Sun’s corona, a solar radiation storm is simply an intensification of the charged ions normally emitted by the Sun as part of the solar wind. Only, in a radiation storm, both the density and speed of the emitted particles get greatly enhanced.

We’re currently still in the peak years of our current sunspot cycle: the 11-year solar cycle that’s been tracked for centuries, where “peak years” see 100+ sunspots on the Sun while “valley years” see a largely featureless Sun. While several notable auroral displays have graced Earth in recent years, there’s only been one other severe (S4 or higher-class) solar radiation storm this century: back in 2003. Whereas most space weather events take around 3-4 days to traverse the Sun-Earth distance, the particles ejected from the Sun early on January 19, 2026 (UTC) were already triggering spectacular auroral displays less than 24 hours later. Here’s the science of how it all happened, and what dangers — and displays — such events hold in store for our world.

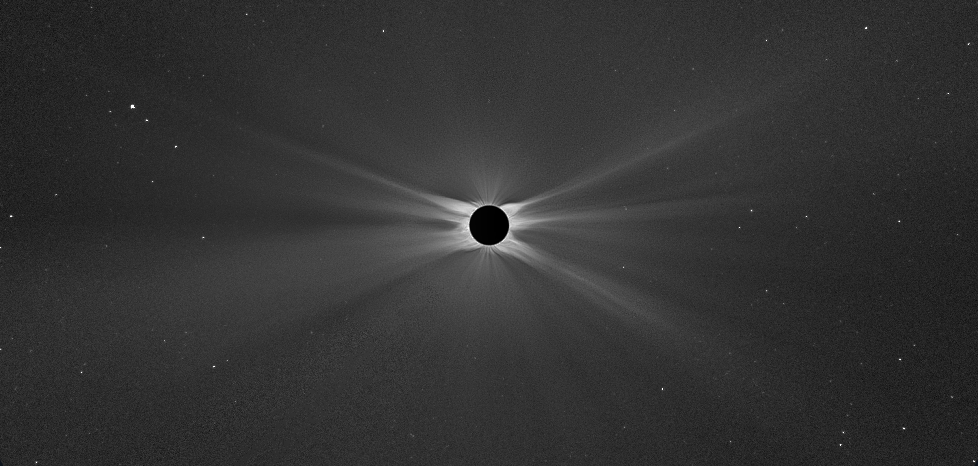

Credit: Martin Antoš, Hana Druckmüllerová, Miloslav Druckmüller

The first thing you should understand — and not only people, but even most physicists, don’t fully appreciate this — is that the Earth, and all of the planets in the Solar System, are actually inside the atmosphere of the Sun. We usually think about the Sun as being a ball of plasma with a wispy, extended atmosphere and a halo-like corona surrounding it, but those are only the locations where the plasma density is the greatest. In reality, the Sun is a powerful enough, hot enough engine that it fills everything inside our heliosphere, which extends out to beyond the orbits of Neptune and Pluto, with that hot, ionized plasma.

While we typically only view the extended atmosphere of the Sun under favorable viewing conditions, like during a total solar eclipse from Earth, or from up in space with the advent of a Sun-blocking coronagraph, we’ve been able to track a wide variety of its effects. We know that it produces light, sure, but it also consistently produces a stream of ions, mostly protons but also electrons, heavier atomic nuclei, and even small amounts of antimatter, known as the solar wind. That solar wind is guided by the Sun’s magnetic field, which is driven by internal processes inside the Sun, and particularly energetic outbursts come when magnetic field lines “snap” and reconnect at, near, just outside, or even fully inside the Sun’s photosphere.

Credit: NASA/SDO

When those magnetic reconnection events occur internally, normally where sunspots are located, a solar flare often results. When those reconnection events occur externally, fully outside of the Sun’s photosphere, a coronal mass ejection often results. But when those reconnection events occur outside the surface but before you reach the corona, it typically just rapidly accelerates the charged particles that exist in that region outside of the photosphere. That creates the conditions for what’s known as a solar radiation storm, which can then be accompanied — usually afterwards — by either a solar flare (if the reconnection propagates backwards to the Sun’s interior) or a coronal mass ejection (if the reconnection propagates forwards to the Sun’s corona).

The 2003 event, known as the Halloween solar storms because they peaked from mid-October to early November, included both solar flares and coronal mass ejections, including the strongest solar flare ever recorded by the GOES (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite) system, and that was the last severe solar radiation storm that affected the Earth. On January 19, 2026, another one occurred, and it indeed was also followed up by an X-class solar flare and a coronal mass ejection. However, solar flares and coronal mass ejections are common; what was highly uncommon was the solar radiation storm, and the ultra-fast (and large flux of) solar wind particles that came towards Earth.

Above, you can see a graph of the solar wind speed just prior to the start of the solar outburst that created the radiation storm. Note that, prior to the initiation of the storm, the solar wind speed was relatively stable and typical: at around 250-300 km/s, or about 0.1% the speed of light. Under these conditions, it takes the solar wind approximately 5-7 days to traverse the Earth-Sun distance. During normal circumstances, we don’t see a major auroral event, and that’s due to the combined facts that:

- the Sun’s magnetic field is weak,

- the Earth’s magnetic field (at least close to Earth’s surface) is strong,

- there’s only a low density of solar wind particles and they move at relatively slow speeds,

- making Earth’s magnetic field effective at diverting the majority of solar wind particles away from the planet.

After all, it’s only when the particles emitted by the Sun strike Earth’s atmosphere, with large fluxes, large speeds, and the needed relative magnetic orientations, that we get spectacular auroral shows.

You might think about those large speeds that accompanied this solar radiation storm and note they’re approximately quadruple the pre-storm speeds of the solar wind, and think, “oh wow, that means an arrival time of just over one day, rather than 5-7 days, for those particles,” and you’d be correct. You might also then ask, “well, what about the density of particles; did that spike during the radiation storm event?” And the answer, fortunately, is recorded in the data as well.

As you can see, the solar wind density is typically quite low: well below one proton per cubic centimeter (p/cm³). Sure, there are occasionally “blips” in the data of a few p/cm³ that last for a minute or so, but in general, the solar wind density is consistent and low. However, during a solar radiation storm, that density can rise precipitously, and on January 19th, it consistently remained at over 10 p/cm³ for more than an hour, peaking at a whopping 28 p/cm³ at maximum. That combination: of large speeds and of large densities, is exactly the recipe you’d want for making a strong auroral show here on Earth.

It’s why, during January 19th, 2026, an auroral watch was announced worldwide, as these particles were expected to be smashing into Earth’s poles. Or, rather, there was a chance that these particles would smash into Earth’s poles. Remember, there’s one more key ingredient that needs to be considered in determining whether a major auroral event gets generated or not: the relative magnetic field between the Earth and the Sun. The Earth’s magnetic field is consistent: it’s well quantified and the strength and location of our magnetic poles only vary a little bit, and slowly, over time. However, the magnetic field of the Sun is complex, and changes rapidly.

One of the key advances of the 2020s — and, in fact, it’s the only new flagship-class National Science Foundation (NSF) facility to begin operations this decade — is DKIST: the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, run by the National Solar Observatory. It provides humanity with our most exquisite, highest-resolution views of the Sun ever, enabling us to construct the best maps of the Sun in real-time, including as the various features across the Sun, such as cells and sunspots, evolve.

Because what we’re observing is light, we can also observe how that light gets affected by the magnetic fields that exist on the Sun at the time that light is emitted. While space is three-dimensional, there’s only one dimension that truly matters when it comes to whether charged particles from the Sun have an effect on Earth or not: the dimension that either aligns or anti-aligns with Earth’s magnetic field. Solar physicists call this the z-dimension, and so the component of the Sun’s magnetic field that points in that direction is known as “Bz,” or the Sun’s magnetic field that’s either aligned (if it’s positive) or anti-aligned (if it’s negative) with the Earth’s.

In general, this magnetic field is close to 0, as measured in units of nanotesla (nT), and so the Earth’s magnetic field serves as a good deflector of those charged particles. Let’s take a look at what the Sun’s (relevant) magnetic field, it’s Bz, was when the solar radiation storm of January 19th occurred.

As you can see, above, prior to the radiation storm’s beginning, the field was negligible: Bz was approximately zero, with only tiny variations. And then, all of a sudden (at right around 19:00 on the graph above), the Sun’s Bz spiked tremendously. It continued to be large in magnitude, but the sign flipped a number of times, particularly during the first two hours after the initiation of the event.

A Bz of greater than 10 nT in magnitude is quite notable; a Bz of over 50 was achieved for a long time in this particular event. When the field was anti-aligned with Earth’s (marked in red in the graph above), or where the field rapidly changed from positive to negative (or from very negative to even more negative), the Sun-Earth connection acts like a funnel, and those fast-moving charged particles emitted by the Sun spiral down along those field lines until they strike Earth’s atmosphere: creating two ring-like showers of particles around each of Earth’s poles. The:

- stronger the field,

- the faster the particles,

- and the better the magnetic connection between the Sun and the Earth,

the more spectacular the auroral show will be. When the first particles arrived here on Earth, those first couple of hours put on a really spectacular show, particularly for observers in the right part of the world: in northern Europe in particular.

But then, the field flipped again: still large (at around +50 nT), but now positive. With this alignment, the particles get largely deflected away from the Earth, and the auroral show fizzles: much to the chagrin of aurora-hunters in the United States and in southern South America. You had to be particularly far north in Canada or at the southern tips of Australia or New Zealand to see anything at all, and even then, the aurorae were faint and unremarkable compared to the truly spectacular events that had graced the skies in recent years, such as May and October of 2024 or November of 2025.

However, the slower-moving material from the solar flare and the coronal mass ejection is still on its way, and may yet produce a nice auroral show for many skywatchers at a variety of latitudes. It will all depend on what the alignment of the magnetic field between the Sun and the Earth is when those charged particles arrive. It should be anticipated that the magnetic field of the Sun, Bz, will remain positive and strong, although it ought to trail off and quiet down to normal levels again, but there’s always a chance for a field reversal event. All it takes is the right alignment, and the particles will go from being largely diverted away from Earth to striking the atmosphere in spectacular fashion.

It’s also worth pointing out two additional pieces of information about these space weather events and their effects on planet Earth.

- First, that this event is probably one of the last ones that will be a major space weather event as a part of this current, now-declining solar cycle. The cycle — for reasons still not well-understood — ebbs and flows in 11-year cycles. The current cycle looks to have already peaked and should decline until about 2031, and then the next peak is expected to arrive sometime around 2036 or so. We’re likely to still have 100-ish sunspots during most of this current year, but we’re unlikely to get back up to 200, which marked the high point back in 2024.

- And second, that space weather events — marked by large numbers of fast-moving charged particles headed towards Earth — have the dual effects of damaging or even potentially disabling satellites located above Earth’s protective atmosphere, while also inflating the atmosphere and leading to an increased drag force on such satellites.

That second effect is often not discussed, but here in the era of satellite megaconstellations, it means that the mid-2030s will likely be a particularly hazardous time for the space environment above Earth. If, as planned, there truly are hundreds of thousands of satellites in low-Earth orbit, and “active collision avoidance” maneuvers become impossible due to a large space weather event, a collision will very likely ensue in a matter of a couple of days or even less. It’s a recipe for disaster with the current “no plans” for such an inevitability.

The increased drag, as you can see above, is also having a substantial effect on some of the most important satellites in astronomy’s history, like the Hubble Space Telescope. Initially launched at an altitude of about 600 kilometers above Earth’s atmosphere, the orbit has steadily but irregularly declined. In particular, the most severe losses of altitude occurred in the early 2000s (at the peak from two solar cycles ago), in the years peaked around 2015 (when the peak of the prior solar cycle occurred), and very severely from 2023 until the present: at the peak of our current solar cycle. It’s very possible that, unless we take measures to boost the orbit once again (as was done deliberately during the first two Hubble servicing missions), the orbit will continue to decline, and eventually, we’ll lose the telescope altogether.

Regardless of how (or whether) we respond to what the Sun is doing, it’s been doing it for billions of years and will continue doing it: generating space weather of all kinds. Solar radiation storms will continue to occur — as well as solar flares and coronal mass ejections — in an 11-year cycle, peaking when there are many sunspots and sending out fast-moving concentrations of charged particles, sometimes directed at Earth, sometimes with strong magnetic fields that anti-aligns with Earth’s own field. They create beautiful auroral shows when that happens, but they also pose big dangers to our electrical infrastructure on Earth and a huge risk to satellites, with the risk increasing the more satellites there are in low-Earth orbit. Now that you know what’s going on, naturally, and what impacts it’s bound to have, it’s up to all of us to forge a responsible path forward.

This article How a solar radiation storm created January 2026’s aurora is featured on Big Think.