Le Journal

Les cyberattaques touchent de plus en plus le secteur maritime !

Elon Musk warns of declining birthrates in China and worldwide

FIFA faces heat over Trump peace prize, issues visa warning

Shekar Krishnan to chair key New York City Council committee

Harvard’s Aravinthan Samuel gets a better look at brains

A team of Harvard and MIT scientists led by Indian American researcher Aravinthan Samuel is developing a new AI-enhanced scanning method to get a better look at brains with microscopes that work more like human eyes. Until recently, the quest to build high-resolution maps of brains — otherwise known as “connectomes” — was stymied by the slow pace and cost of powerful electron microscopes capable of systematically capturing neuroanatomy down to billionths of a meter. But now Samuel’s team has found a way to bypass that bottleneck: using machine learning to guide a simpler, less-expensive variety of microscope in real time, according to Harvard News. The idea is to home in on key details first and minimize time spent on areas of lesser interest — the same way we might zero in on words on a page instead of margins. Researchers say the innovation, known as SmartEM, will speed scanning sevenfold and open the field of connectomics to a broader research community, boosting our understanding of brain function and behavior. “SmartEM has the potential to turn connectomics into a benchtop tool,” said Samuel, a researcher in the Department of Physics and Center for Brain Science and one of the senior authors of a new paper published in Nature Methods. READ: India-born Henna Karna selected to Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative (September 5, 2025) “Our goal is to democratize connectomics,” he says. “If you can make the relatively common single-beam scanning electron microscope more intelligent, it can run an order of magnitude faster. With foreseeable improvements, a single-beam microscope with SmartEM capability can reach the performance of a very expensive and rare machine.” The method is the product of a five-year collaboration between researchers at Harvard, MIT, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and microscope manufacturer Thermo Fisher Scientific. In December, the same journal proclaimed electron microscopy-based connectomics its “Method of the Year” for 2025 and cited SmartEM an example of cutting-edge innovation. SmartEM marks a new advance in the decades-long quest to create “wiring diagrams” of brains from across the animal kingdom, from worms to fruit flies to humans. Two years ago Harvard researchers published the first nanoscale map of one cubic millimeter of human brain, according to Harvard News. Packed into that poppy-seed-sized sample were 150 million synapses, 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and a wondrous diversity of structures never seen before. Researchers elsewhere have completed connectomes for the fruit fly and zebrafish. The next grand challenge is one for the mouse, according to Harvard News. To build these maps, scientists have relied on a technique known as serial-section electron microscopy It entails shaving samples of brain tissue into thousands of ultra-thin sections, which are then scanned and imaged by powerful electron microscopes. Next the images are stacked on top of each other to create 3D digital replicas. For example, that one cubic millimeter of human brain tissue published in 2023 was sliced into more than 5,000 sections, each thinner than one-thousandth of a human hair. These endeavors pose monumental technical hurdles for both capturing the images and processing the data. Until recently, connectomics had been the exclusive purview of a small number of researchers and institutions that can afford multimillion-dollar hardware such as high-throughput electron microscopes with up to 91 beams. With growing demand to generate brain maps of many species, one obvious way to push forward connectomics is to recruit more microscopes — particularly single-beam electron microscopes, which are widely available at research institutions around the world. READ: Harvard students to host India Conference in Feb. 2026 (December 1, 2025) Their speed largely is a function of the “dwell time” that the beam devotes to each pixel. In the standard approach, specimens are scanned with the…

One dead, democracy in critical condition following Minnesota shooting

Indian American couple charged in Dumfries motel sex trafficking, drug case

The dilemma of destiny as our own prisoners: What MLK would tell us

What MLK knew about the game Martin Luther King Jr.’s leadership through the lens of game theory, argues that his commitment to disciplined nonviolence was not only moral, but strategic—a deliberate attempt to move society out of a bad equilibrium such as the famous game theory called “The Prisoner’s Dilemma,” from Martin Luther King’s “Game Theory,” in the January edition of The Wall Street Journal. The Prisoner’s Dilemma theory has endured for more than seven decades not because it is clever, but because it is still relevant to many situations we confront in our daily lives. At its most basic level, the problem captures a paradox that plays out repeatedly in our lives — where rational individuals and institutions, acting independently and in good faith, can produce outcomes that are predictably worse for everyone involved. Here we look at how the Prisoner’s Dilemma applies to the affordability crisis for everything from homes, to health to food. King understood what The Prisoner’s Dilemma shows that when people act alone, everyone sticks with self-interest and the status quo continues; when expectations change, cooperation becomes possible. By consistently showing restraint and trust, he shifted how others weighed risk and reward. The lesson is clear today. In healthcare, food, housing and many other areas we are not stuck because cooperation is impossible, but because no one has yet changed the system to make working together safe. Whether it’s healthcare, housing or food, millions of people are struggling to survive because life has become simply too expensive. In this game, the prisoners are not abstract actors but all of us—consumers, patients, workers, employers, insurers, providers, developers, lenders, and policymakers each making rational, self-protective decisions within our own silo, yet collectively sustaining a system that makes basic necessities increasingly unaffordable. The Prisoner’s Dilemma is prison is different from theory The formal structure of this game theory was developed in 1950 by mathematicians Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher at the RAND Corporation as part of early work in game theory, and it was later framed and named by philosopher and mathematician Albert W. Tucker. In its original version, two prisoners are interrogated separately and offered incentives to betray one another. Each person faces a choice of defection that minimizes their own punishment if the other defects, yet when both choose it, the result is worse for each than if they had cooperated. Game theorists quickly understood that the model was never really about crime. It was about coordination failure in situations where cooperation would lead to better outcomes. One is left to wonder whether the architects of The Prisoner’s Dilemma had ever set foot inside an actual prison. Because the central choice the model hinges on—cooperate or “snitch”—rarely exists in the way the theory imagines. Inside prison, there is an unwritten code: cooperation through silence is expected, and betrayal carries consequences that extend far beyond the immediate transaction. The mantra is simple “stay in your lane” and snitches get stitches. The dilemma, in prison, is not whether to cooperate, but whether one is willing to live with the long-term social cost of defection. Those that have cooperated in criminal cases never really knew the consequences of breaking the code until it was too late. Are we all captive in our cells? The real insight of the theory, then, is not about just prisoners, but about how people and institutions behave when they operate in vacuums—isolated from one another, stripped of shared context, and guided by incentives that reward self-protection over collective benefit. This distinction matters because it reveals a flaw in how we often apply economic and policy models. In some ways, we all live in our own cells. Game theory assumes people make rational choices in isolation. In real life, people make decisions inside social…

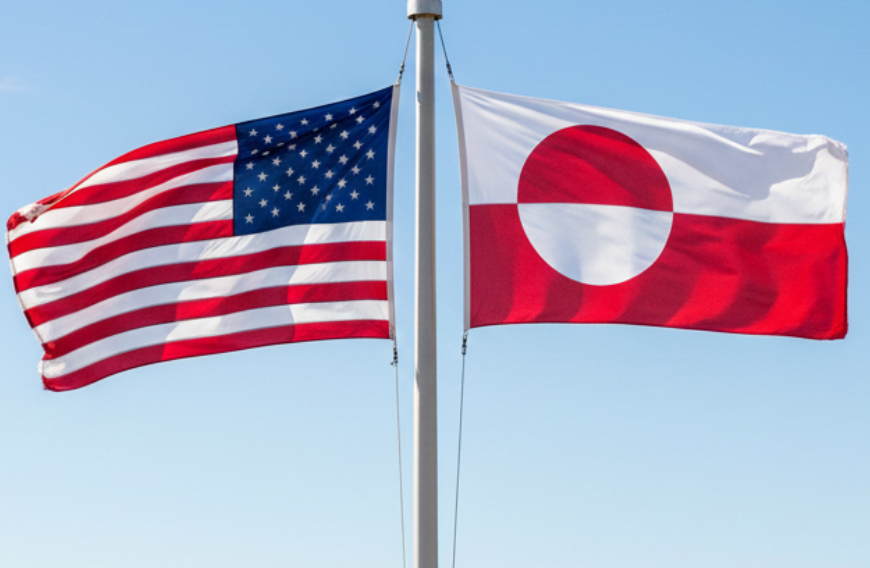

Europe pushes back as Trump threatens new tariffs over Greenland

Mamta Singh takes oath on Bhagavad Gita in Jersey City

Analysis: Mississippi hits 99.7% school meal dependency