Here in the Universe, there’s a fascinating property that nearly every galaxy beyond our own Milky Way seems to possess: the light that we observe from it seems to be shifted toward redder, longer wavelengths than the light that’s emitted from within our own galaxy. Within the context of general relativity, there are a number of possible explanations for an observed redshift: it could be due to the relative motion of the source and the observer, it could be due to a difference in the curvature of space between the source and the observer, or it could be due to the fabric of space itself stretching and expanding as light travels through it.

Yet, if it were the effects of gravitational masses (like galaxies) tugging on other masses (like other galaxies) that dominated the Universe, you’d expect that there would be equal numbers of galaxies that are redshifted as compared to blueshifted, and yet there are far fewer blueshifted galaxies, and almost none at all that are very far away from us. Why is that? What do those observations teach us, and are we interpreting them correctly? That’s what Bob Millar wants to know, writing in to ask:

“We understand that the universe is expanding, and we see that galaxies are retreating from us at speeds related to their distance. But what is the geometry that makes it so that we don’t see objects moving toward us at blueshifted rates? […] I can’t envision the situation where everything moves away but nothing seems to come toward us.”

This is a very deep question, and what we’ve learned over the past century — about as long as our notion of the expanding Universe has been around — has taught us so much about the Universe we inhabit. Here’s what it all means.

A lot of people begin by trying to visualize how the Universe expands, and then attempt to add in and reconcile the idea of the redshifting of distant galaxies within it. But historically, of course, this is not how the idea developed at all. Back in the early 20th century, we didn’t know whether the Universe was expanding, contracting, or static, or whether anything other than the assumed “static” was even an option. We also didn’t know how big the Universe was and whether it extended beyond the Milky Way galaxy itself, or whether the galaxy that we inhabit was the entirety of the Universe itself. There was even a “great debate” about the latter issue held in 1920, leaving no clear winner: only a series of interpretations about inconclusive data.

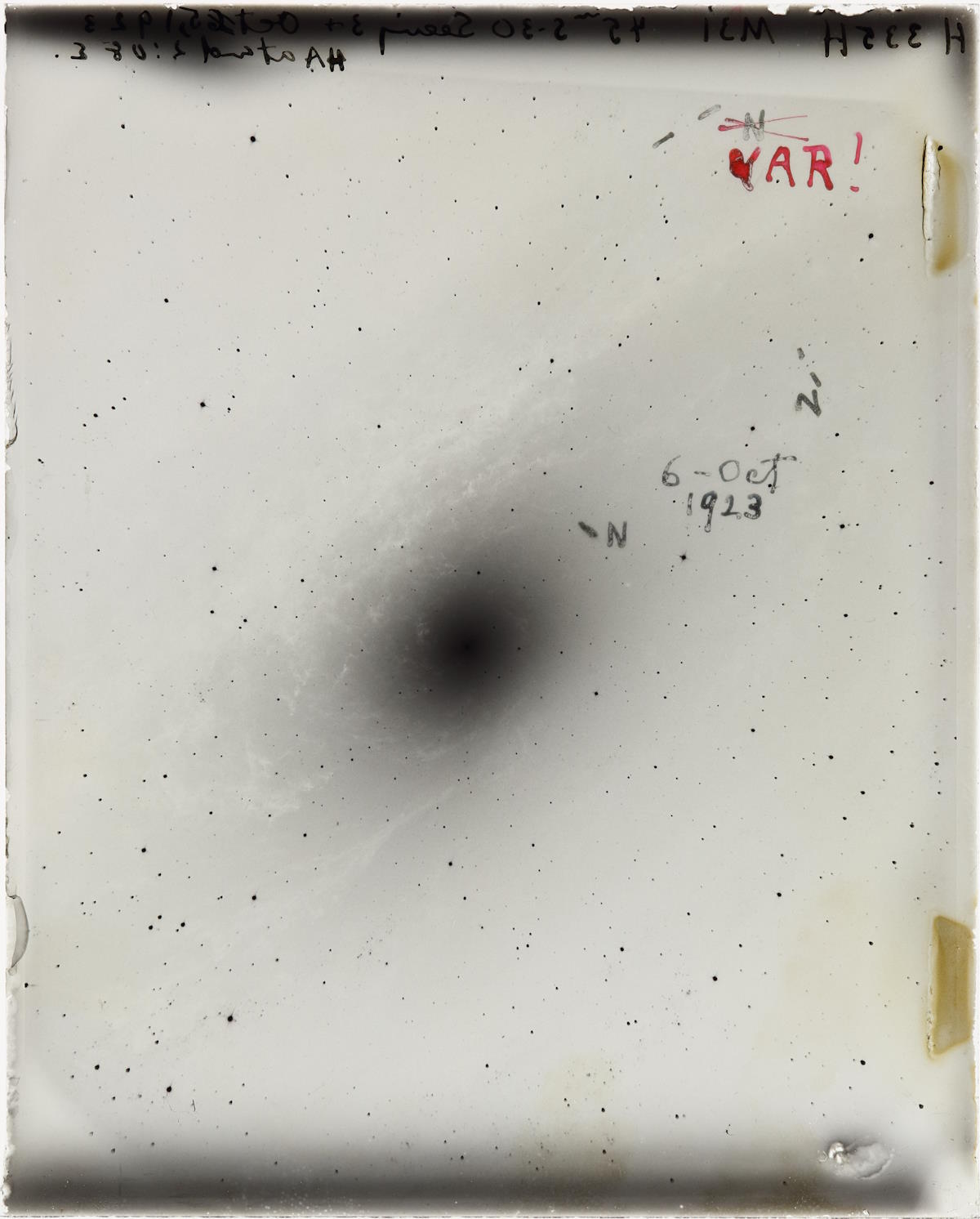

This began to change in 1923, however. Edwin Hubble, using the then-largest telescope in the world (at 100″ in diameter for its primary mirror), spent some of his nights observing the great nebula in Andromeda: now known as the Andromeda galaxy, but at the time it was thought by many to be a nebulous object within our own Milky Way. Hubble was looking for novae: outbursts where white dwarf stars accumulate enough matter on their surfaces to trigger a brief burst of nuclear activity within them, leading to an intense brightening. He saw one brightening event, marking it with an N, and then a second, and then a third.

And then, less than 48 hours later, he saw a fourth event: one in the exact same location as the first event. Excited, he crossed out the N, and then in big red letters, wrote the most famous annotation in astronomy’s history: “VAR!”

This was a revolutionary discovery. Novae take extremely long times to recharge, with even the shortest-period nova known today recurring only after several years have passed. (Most take centuries, millennia, or longer.) But what appeared to brighten like a nova instead rebrightened again in a span of hours, not years or even longer. This told Hubble that his earlier assumption was incorrect; it couldn’t have been a nova that he observed. Instead, to brighten and fainten and brighten again in just a matter of hours or days pointed to a different culprit: a class of variable stars known as Cepheid variables.

With this new interpretation of the data, Hubble began searching for more and more variable stars in Andromeda, and he found them: far fainter than the variables within the Milky Way, but brightening and faintening by the same relative amounts as the stars within our own galaxy did. This led him to determine the distance to Andromeda: not hundreds or thousands of light-years, but more in the ballpark of a million light-years. (The modern value comes out to about 2.5 million light-years.) At last, we knew that the Milky Way didn’t encompass the entirety of the Universe, but that there were other galaxies out there beyond our own.

There were a great many spiral nebulae that had been identified in the skies; Andromeda was merely the first one to have an astronomical distance put to it. If you were to visualize a Universe that was vast, filled with galaxies, and also that was roughly uniform in density — where the mass densities and number densities of galaxies on large-scales were similar at all locations — then you’d imagine that it would be the cumulative effects of gravitation that determined how these galaxies were moving. In three-dimensional space, the overdense regions would draw large numbers of galaxies into them, while the underdense regions would give up their matter to the less dense regions.

From our perspective within the Milky Way, that line of thinking would lead to us being able to observe only the relative motions of these galaxies along our same line-of-sight. The ones that were moving toward us would be seen to have a blueshift; the ones moving away from us would be seen to have a redshift. Because gravity, in a Universe that has matter randomly distributed throughout it, is just as likely to create “toward-going” motions as it is to create “away-going” motions, you’d expect that just as many galaxies would have redshifts as blueshifts.

But even in the time of Hubble, observationally, this was known to not be the case. While nearly as many stars within the Milky Way have blueshifts as redshifts as observed by us, nearly all of the spiral nebulae, elliptical nebulae, and other, irregular objects that we now identify as galaxies external to our own were observed to have redshifts, with blueshifts being incredibly rare.

Moreover, there was an interesting trend that seemed to be emerging among these galaxies, particularly as we began to measure the distances to more and more of them. With variable stars spotted in increasingly more and more distant galaxies, it appeared as though it was only the absolute nearest ones that tended to have any chance of being blueshifted at all. The farther away you went, to distances of tens of millions of light-years rather than just millions of light-years, the greater the percentage of galaxies that exhibited redshifts, and the smaller the percentage of galaxies with blueshifts. Moreover, the average redshift appeared to be larger: increasing with increased distance.

At distances of between 50 and 100 million light-years, only a small fraction of galaxies — and even at that, only ones found within quite massive galaxy clusters, and hence the ones experiencing the largest local gravitational influences — have a blueshift to them. And again, at greater distances still, the average redshift of galaxies was even larger. At distances exceeding 100 million light-years, only very close to the centers of the largest, most massive galaxy clusters of all do we find any galaxies with a blueshift to them: the ones that happen to be getting “pulled” in our direction more quickly than the general redshift trend at those distances imparts.

Finally, beyond distances of 300 million light-years, there are no blueshifts to any known galaxies at all. No matter where a galaxy is located, even with the most extreme peculiar (locally gravitationally induced) velocities possible, every galaxy is observed to have a redshift.

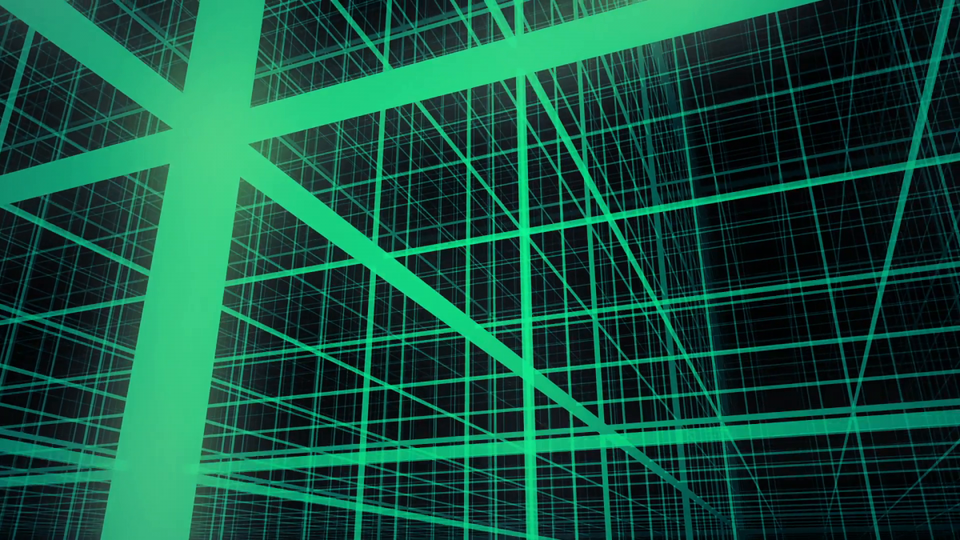

In fact, this notion of a redshift-distance relation goes back even before Hubble published his major results showing the existence of this relation in 1929; Georges Lemaître beat him to the punch back in 1927. Lemaître’s paper didn’t just piece together this evidence — two full years before Hubble himself did so, by the way — but actually did the heavy lifting of the theoretical work to explain why. Back in 1922, a theorist named Alexander Friedmann had worked out what happens if you have a Universe that’s uniformly (or nearly uniformly) filled with matter, radiation, or any species of energy.

Unlike all prior attempts to do such a calculation, however, he did it within the context of general relativity, not Newtonian gravity, as Einstein had only released general relativity into the world in 1915, and this calculation was far more difficult than any of the other exact solutions that had been found up to that time. What Friedmann found was that:

- a Universe that is governed by general relativity cannot be uniformly filled with matter or energy of any species and be both static and stable,

- that instead, such a Universe must either expand or contract globally,

- and that whether any such Universe would expand forever or recollapse depended on how fast its expansion rate was, and what the various densities and types of energy present were and how they compared to the expansion rate.

When Lemaître wrote his 1927 paper, he was aware of Friedmann’s earlier work, and was the first to apply actual data about the Universe itself to this new set of solutions in general relativity. He plotted out the distances to the various galaxies (from Edwin Hubble’s early work) and the measured redshift of those galaxies (from Vesto Slipher’s independent work), and put all the pieces together.

- The farther away a galaxy was, on average, the greater the observed redshift of that galaxy.

- This corresponds to a Universe that is expanding, rather than contracting or remaining static.

- If the Universe is expanding today, that means it was smaller and denser in the past, and also hotter.

- And if you extrapolate back far enough, you’ll arrive at a “zero size” for the Universe, corresponding to infinite temperatures and densities: to a state known as a singularity.

It was Lemaître who drew each of these conclusions, and he did it alone: dependent on the earlier work of others, but with his own mind and with publicly available data. This represents the origin of the idea known as the Big Bang, and the first observational evidence in support of the notion of the expanding Universe. Even though the name “Big Bang” wasn’t coined until years later, the concept was born back in 1927, when more poetic names like “the primeval atom” or “the cosmic egg” were more common.

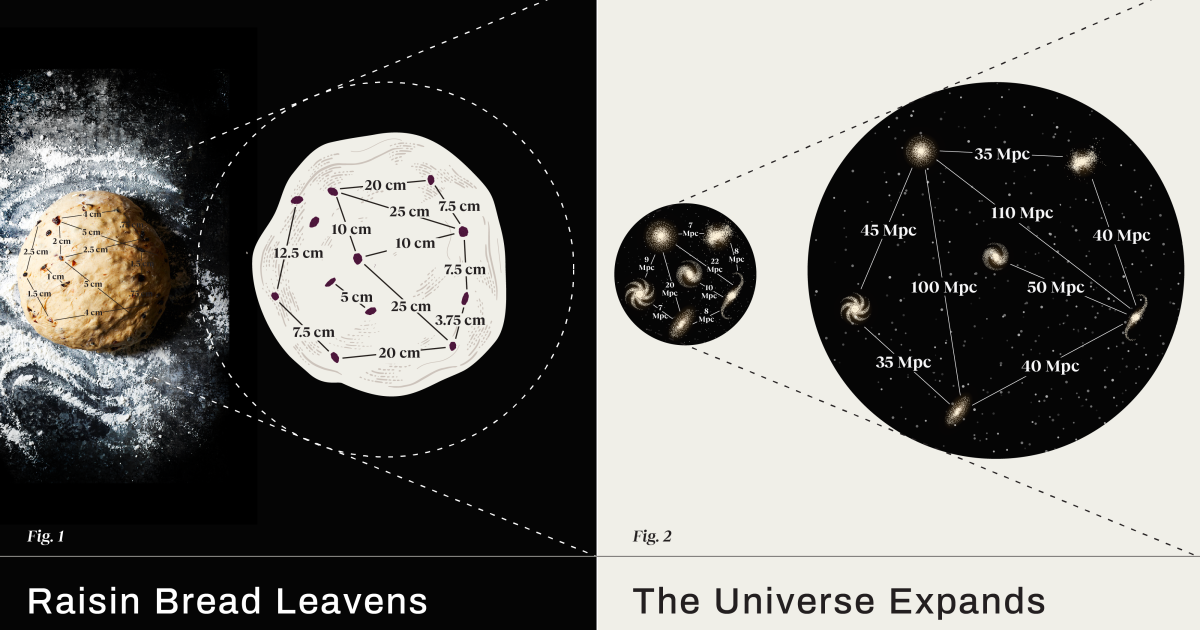

It’s easy to understand why the Universe was denser in the past and why it will get less dense into the future as it expands: because the volume of space that the (unchanging) number of particles within it occupies changes. It was denser in the past because the same number of particles existed inside a smaller volume, and it will be less dense in the future because the same number of particles (or galaxies) now occupy a larger volume.

But for radiation, the story is a little different than it is for matter. Yes, the number of radiation particles decreases as the Universe expands, and the number density of radiation particles was greater when the Universe was smaller: the same as for matter. But for radiation, the energy of every quantum of radiation — i.e., the energy of each individual photon — is defined by its wavelength.

When the Universe expands and radiation travels through it, then the expanding fabric of space causes the wavelength of each individual photon to stretch, and therefore, to lengthen. The longer a photon travels through the expanding Universe, and they have to travel for longer to reach you if they were emitted by a galaxy that’s farther away, the more its wavelength stretches. And that’s why the farther away a galaxy is, on average, the more we see that its light is redshifted.

At present, we’ve measured the expansion rate of the Universe very well, and even with the great uncertainties induced by the modern puzzle of the Hubble tension, we can be confident that the Universe’s expansion rate is around 70 km/s/Mpc, which means for every megaparsec (about 3.26 million light-years) away that a galaxy is, its light will correspond to a redshift that’s the equivalent of a source moving away from the observer by 70 km/s. That means by looking at a galaxy that’s:

- 10 million light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 215 km/s,

- 50 million light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 1074 km/s,

- 300 million light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 6440 km/s,

- 1 billion light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 21,500 km/s,

- 5 billion light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 107,000 km/s,

- 14 billion light-years away, we expect it to have a redshift that corresponds to a recession of around 300,000 km/s (the speed of light),

and so on.

On the other hand, gravitational redshifts, which are due to the difference in gravitational potential between the emitting source and the observer who sees the light, generally cap out at a maximum of around 1-part-in-1,000,000, and so can only induce redshifts that correspond to ~1 km/s at most. The other major effect, of the peculiar velocities induced by large masses that are nearby, are typically on the order of a few hundred or a few thousand km/s, with the greatest departures from the general expanding Universe (also known as the Hubble flow) around ±6000 km/s.

Credit: V. Wetzell et al., Dark Energy Survey, MNRAS, 2022

In the very nearby Universe, such as within our Local Group, you’re just as likely to find a blueshifted galaxy compared to a redshifted galaxy. Even Andromeda, the very first measured galaxy outside of our own, has a blueshift and not a redshift. But as you look to objects that are farther and farther away, the expansion of the Universe becomes increasingly more important. Most of the galaxies outside of the Local Group are receding from us, and hence have a redshift, while only a few galaxies, mostly in groups and clusters that are nearby, have a blueshift to them. There are some prominent ones in the Virgo cluster, the most distant ones are at the distance of the Coma cluster, and there are practically none beyond that.

That’s because, while it may be possible for galaxies to be heavily influenced by whatever gravitational clumps, voids, and other overdensities/underdensities are present nearby, there’s a limit to the amount of speed that can be imparted to them within the expanding Universe: capping out at around 6000 km/s. For galaxies more distant than a few hundred light-years away, the shifting of their light is dominated by the effects of the expanding Universe, and by the Hubble expansion of the Universe itself. The farther away you look, the greater the effects of the expanding Universe on the light that’s arriving now, and that’s why, for the most distant galaxies of all, there isn’t a single one that exhibits a blueshift of any kind.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithagbang at gmail dot com!

This article Ask Ethan: Where are all the blueshifted galaxies? is featured on Big Think.