Fantasy is a dominant genre in the tabletop RPG space. From Dungeons & Dragons to Pathfinder to Daggerheart, if players go to the local store and ask about playing an RPG, they’re probably going to be sold on big, epic fantasies about heroic characters in ruin-filled, magical worlds. The indie space is just as fantastical, with games like Mythic Bastionland and Dolmenwood taking their own unique turns at responding to the big fantasies with smaller, weirder ones. But what happens when players want to make fantasy worlds as much as they want to play fantasy characters? And what if they’re interested in post-fantasy—taking all the assumptions of fantasy and turning them on their head, playing with the influences, and injecting some friction into the typical swords-and-sorcery, plains-and-mountains worlds? They should probably play A Land Once Magic.

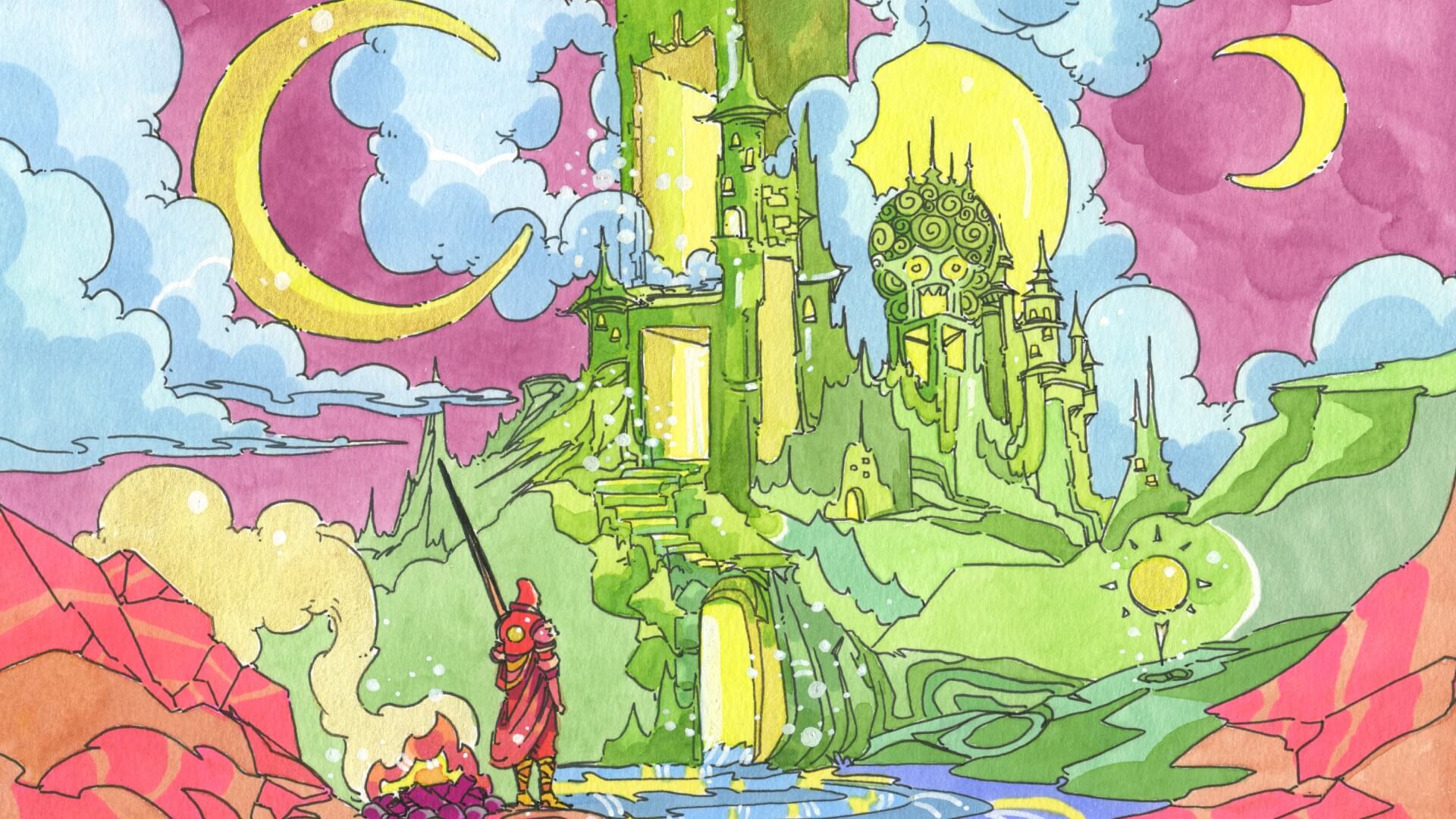

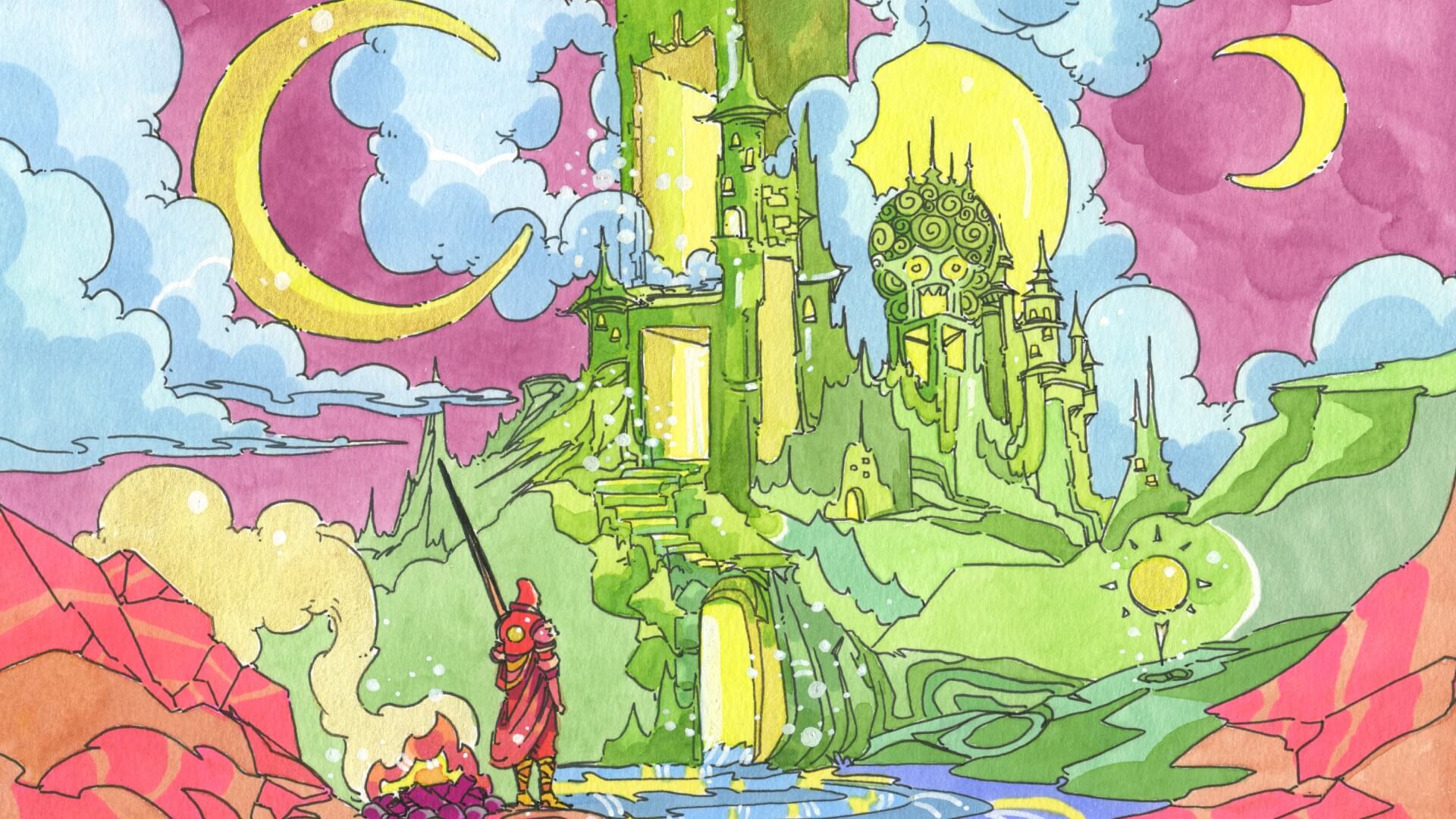

Viditya Voleti’s A Land Once Magic, five years in development and recently released in both a regular and a prestige format by More Blueberries, is a world creation game for two or more players. It asks players to use a standard deck of cards to make a fantasy world from the ground up, and it provides a number of prompts and tables to ensure that those players make their fantasy weird, or at least outside of the standard fantasy usually found in the average D&D core rulebook. Veteran designer Voleti is explicit about this in the opening of the rulebook: the game is, in essence, a provocation to the genre, asking “how do we move fantasy in a new direction?”

This movement is guided very directly by the game itself. It first asks players to create a palette of tones and flavors (paints) that can be invoked in the game. These are the things that will be returned to repeatedly in order to justify the shape of the world and to think through the implications of the cities and cultures that players place into it. The rulebook suggests things like raw, jagged, and cluttered, all adjectives that feel very different from the influence of fantasy stalwarts like Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films. An engaging idea, the palette does some interesting parameter-setting that’s more purposeful than the assertion-based game mechanics of worldbuilders like Microscope or The Quiet Year. Creating a palette is creating a series of purposeful limits about the aesthetic space of a world, and it’s easy to envision doing it in a profoundly limiting way that would produce some off-kilter fantasy: dead, unmoored, or drained, perhaps.

In addition to the palette, the game explicitly asks for players to come up with touchstones that are outside of fantasy. It’s commendable when a tabletop game recognizes players are all coming to it with their own assumptions about the world. They’re chasing Conan, Earthsea, or whatever their favorite fantasies are, and most games are content to provide a list of films and books with the right vibe for the game and call it a day. A Land Once Magic mechanizes the contexts players bring to the game, and more than that, it encourages them to import entire aesthetic packages and translate them into the fantasy frame. The rulebook offers “Cowboy Bebop’s Jazz and Bluegrass soundtrack” as a touchstone, for example, and thinking about it for a few minutes can produce a host of delightful, nontraditional fantastical setups: “Heat’s crowded, amoral landscape” or “a lush, full sense of being hunted by a Predator.” Maybe “the smirking nihilism of a Vince Staples album.” Figuring this out, and getting everyone at a table to agree about it, might be the hardest thing to do for a random group of people playing A Land Once Magic, but also figuring it out, and applying it judiciously, is the thing that makes this game unique and grippy over some of the other worldbuilders in the tabletop space.

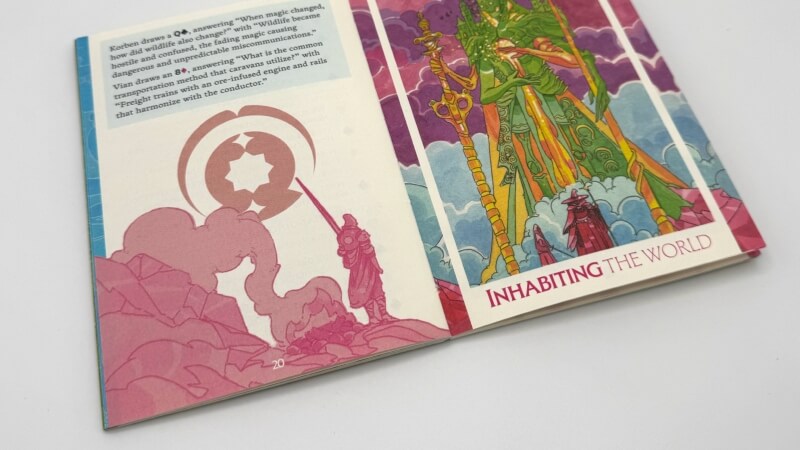

The rest of the game plays predictably for anyone who has experimented in this space. Players draw cards from a deck, and they use those cards to produce prompts that players have to respond to. They justify those responses using the palette and the touchstones. Players begin from the biggest, broadest part of the world—its magic—and progressively move through cities, journeys, and even down to individual characters, which makes the logical end of the game playing an RPG with their new world that they have built.

What’s most enjoyable about A Land Once Magic is that its worldbuilding process asks players to complete sentences more than just taking on information. The game rarely explains the shape of the world, but it makes some statements that players use their own materials to fill in the details for. For example, while working on “A City,” which generates a major locale for players to interact with, a player is instructed to draw a card to answer the prompt of “Its influence was…”; when they draw a spade the provocation they receive is “laws.” Thinking through their palette from before, and the touchstone about Predator, they might say that the capital city of this land was a place of justice, a haven for those who want to be valorized for their actions and moral uprightness in a world of violence. That has also made the city cluttered and compact, given the violence and difficulty of the hunt-or-be-hunted reality in the wilds and villages beyond. Wow, look at that! They just did some worldbuilding, and it’s at least notionally interesting. Then the game would ask the players to choose if this was a city on the way up or down, and they’re off to the races creating a fascinating backdrop for whatever story they want to cook up together.

A Land Once Magic excels as a tool for making a world. It’s a quick game that can be played in 45 minutes with friends at a bar, or it can be a weekly four-hour session with friends in place of board games or a long combat session against Strahd. The game thinks very clearly about its off ramps, and it also includes a series of exploratory tables that prompt players into thinking about the internal logics of their world; it’s not hard to see that accruing into adventure hooks for later RPG play, or even building onto preexisting campaigns