Le Journal

Gov. Mills traveled outside of Maine as ICE operation began. Her team won’t say why.

Saco to hold public hearing on RV camping ordinance

Our most anticipated films of Sundance 2026

5 songs you need to hear this week (January 22, 2026)

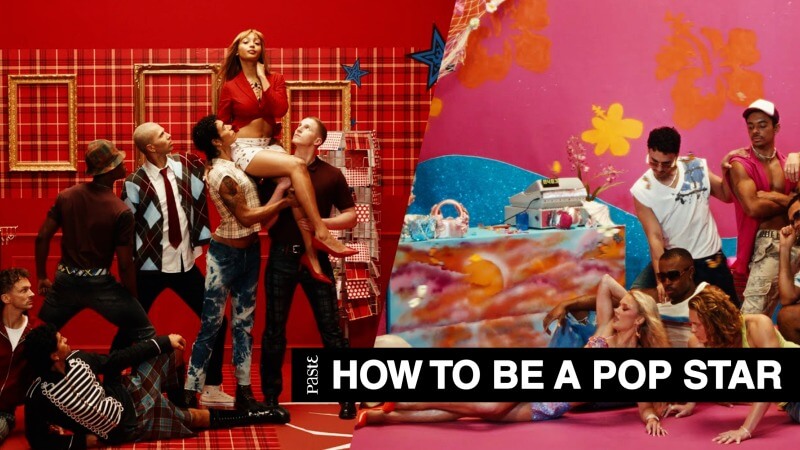

Only YOU can save music videos

I’ve been thinking about music videos a lot lately. Right at the start of the new year, when most of us were watching the ball drop or popping bottles and sipping bubbly at the clurb or, let’s be real, rewatching When Harry Met Sally for the 30th time, MTV shut down all its music-only channels—including MTV Music, MTV ’80s, and MTV ’90s—in the UK and Australia. For music fans online, the news signaled the death of the music video. But then again: Did it really? After all, how many people were still watching MTV by the end? I mean, who even has cable these days? (I suppose you could’ve watched MTV on Pluto too, but what the hell is Pluto, anyways?) My suspicion that this all amounted to a cultural nothingburger was partially confirmed by the fact that so many of the eulogies bemoaning MTV’s demise got so many of the basic facts wrong: MTV still exists, at least as a channel that mostly hosts an agonizing assortment of reality TV shows (which is its own topic of conversation, but I digress). Even the music-only channels still exist on cable in the US right now, although those are slated to go dark throughout this year as their distribution contracts expire. And so MTV isn’t really “dead”—at least, not in the way that news outlets and music fans online seemed to be implying—and the fact that very few of the people relentlessly mourning MTV clocked the fact that it was still alive in the US suggested, to me, that no one was turning on their TVs to actually watch MTV in the first place. In reality, MTV has been dying a long, slow death for a while now, its cultural relevance fading with each year. I suppose that’s just not as exciting a story as the ‘90s nostalgia thinkpieces that the MTV announcement spawned. Perhaps more importantly, though, YouTube announced in December that it would no longer provide its video streaming data for Billboard’s various charts. The decision was based primarily on YouTube’s disagreement with Billboard’s method for counting music streams, where paid streams (ex: a Spotify Premium stream) are weighted more heavily than free or ad-supported streams (ex: a free YouTube stream.) YouTube wanted both paid and ad-supported streams to be weighted equally, and even though Billboard did agree to slightly bump up the weight on ad-supported streams, it wasn’t enough to reach an agreement with YouTube. Thus, as of January 16th, Billboard officially no longer uses YouTube streaming data for its charts. And if we were going to worry about music videos, that feels like the real tea leaves to read. Perhaps I’m biased in my viewing of this YouTube announcement as a more crucial indicator for the culture; after all, I came of age in the 2010s, when YouTube VEVO channels had effectively already replaced MTV as cultural and musical kingpins. The biggest videos from that era of VEVO world domination still have absolutely mind-boggling view counts: 8.9 billion for “Despacito,” 6.9 billion for “See You Again,” 5.7 billion for “Uptown Funk.” YouTube is how I remember encountering so many music videos in my own childhood: Nicki Minaj’s candy-colored, hallucinatory “Starships,” Rihanna’s Requiem for a Dream knock-off “We Found Love,” even Avril Lavigne’s flop “Hello Kitty” (which, years later, is very fun in an unbearable sort of way). Part of the reason why some music videos from that period have such high view counts is simply because those songs were popular. Before the true rise of streaming services, watching music videos on loop was the closest you had to “streaming” itself. Music videos were a crucial means of consuming music, so everyone watched them; that’s probably how you found a lot of music at that time, regardless of the quality or memorability factor of the videos themselves. Even held at gunpoint, I couldn’t tell you what actually happened in Justin Bieber’s “Sorry” music video (4 billion views) without rewatching it, but God knows I watched it to hear the song then. For all the hand-wringing that came with MTV…

Sam Claflin is The Count Of Monte Cristo in teaser for new Masterpiece PBS series

Ruin the picnic in the tricky ant-based board game Gingham

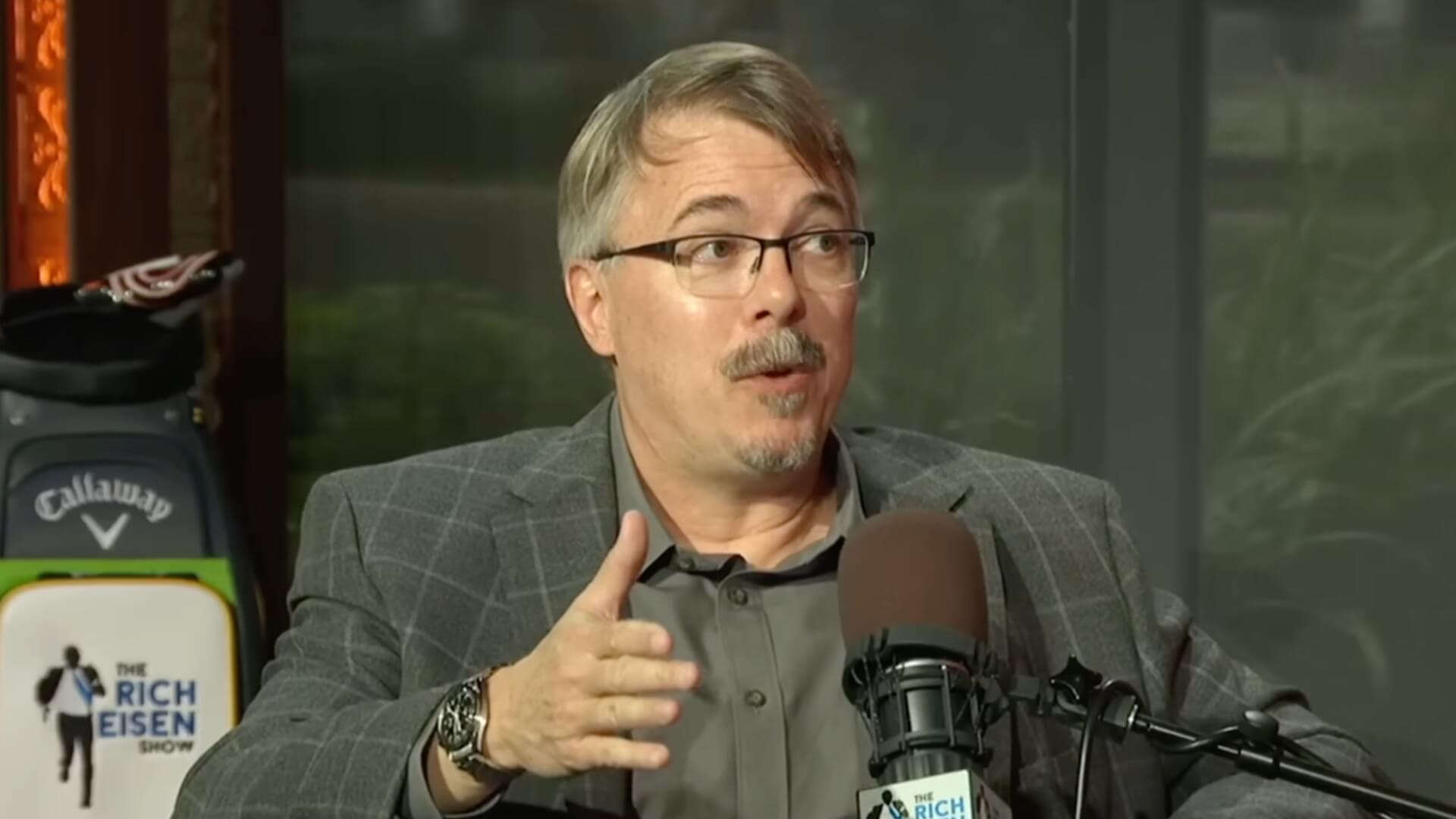

Vince Gilligan, R.E.M, 700 other artists sign open letter condemning AI "theft"

As AI invades more creative spaces, whether we ask it to or not, a coalition of actors, musicians, writers, and other artists have shared a new statement with a blunt message: stealing isn’t innovation. “America’s creative community is the envy of the world and creates jobs, economic growth, and exports. But rather than respect and protect this valuable asset, some of the biggest tech companies, many backed by private equity and other funders, are using American creators’ work to build AI platforms without authorization or regard for copyright law,” reads the statement. “Artists, writers, and creators of all kinds are banding together with a simple message: Stealing our work is not innovation. It’s not progress. It’s theft – plain and simple. A better way exists – through licensing deals and partnerships, some AI companies have taken the responsible, ethical route to obtaining the content and materials they wish to use. It is possible to have it all. We can have advanced, rapidly developing AI and ensure creators’ rights are respected.” The letter has already received about 700 signatures, according to Deadline. Some of the names we recognized, in no particular order, include Vince Gilligan, Winnie Holzman, OK Go, Olivia Munn, Cyndi Lauper, Jennifer Hudson, They Might Be Giants, Sean Astin, George Saunders, Scarlett Johansson, Kristen Bell, R.E.M., Alex Winter, Cate Blanchett, Chaka Khan, Bonnie Raitt, Aimee Mann, and Fran Drescher. The question of AI theft has been circulating for years now and likely isn’t going away any time soon. While massive companies like Disney have the option to enter into lucrative deals with OpenAI (after dubbing a rival AI company a “bottomless pit of plagiarism”) the majority of actors, novelists, and whoever else does not have this option. Last year, a group of writers brought a lawsuit against Anthropic AI, alleging that the tech used their copyrighted writing without permission or payment to train its Claude model. The company settled that lawsuit in August.

The Adams family confronts death with heavy-metal style in Mother Of Flies

First full Masters Of The Universe trailer finds He-Man working in HR

All the nominees at the 2026 Oscars