Le Journal

Look of the Week: The surprising elegance of Renate Reinsve’s red carpet bandana

BREAKING: The Buffalo Bills Have Fired Sean McDermott

Trump’s Letter to Norway Should Be the Last Straw

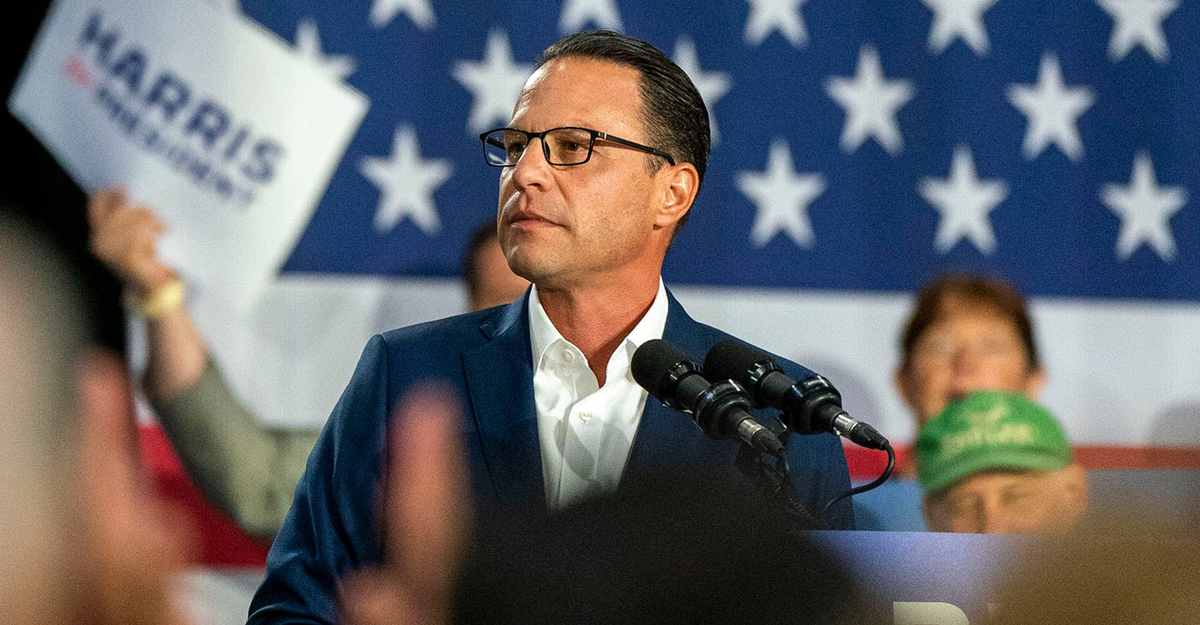

Welfare Fraud Is a Problem—For Democrats

Those Who Try to Erase History Will Fail

Belzoni, Mississippi, a town of about 2,000 people, is known as the “Catfish Capital of the World”; it is also known as the site of one of the first civil-rights-era lynchings. On May 7, 1955, two members of the local White Citizens’ Council shot into the cab of Reverend George Lee’s car; the bullets ripped off the lower half of his face. Lee had been a co-founder of the town’s NAACP chapter and the first Black person to successfully register to vote in Humphreys County since Reconstruction. He’d also registered about 100 of his fellow Black citizens to vote, a remarkable feat given Belzoni’s size and the ever-present threat of violence against Black people throughout the South who dared to exercise their franchise during the Jim Crow era.The Mississippi NAACP, led by Medgar Evers, began to investigate the death as a murder. But the county sheriff rejected the idea that there had been any foul play, instead suggesting that Lee had died in a car accident and that the lead bullets detected in his jaw were simply dental fillings. The local prosecutor refused to move forward with the case, and the white men went free.I learned this story recently, after visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice—known to many as the National Lynching Memorial—in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial consists of more than 800 rectangular steel pillars, each representing a different county in which a lynching took place. One of them is Humphreys, in Mississippi.[From the June 2024 issue: The lynching that sent my family north]It was a cold, rainy day, and my first time seeing the memorial. The space is haunting in its stillness, and overwhelming in its scale. Some of the steel pillars are suspended from above, while others are closer to the ground, forcing you to walk among them, through a steel labyrinth of racial terror.A man named Lee Perkins was also at the memorial that day, being pushed around in a wheelchair by his son-in-law Chris Brown. Perkins was born in Belzoni in 1937. He was 17 when the lynching took place. As he told me about growing up as a Black child in the Mississippi Delta, he looked up, his eyes tracing the pillars’ long, still bodies. He had a coarse voice with a warm southern drawl. “I never thought I would see something like this,” he said, his neck craning to read the names on each piece of steel. Dusk began to settle around us, and the sky slowly darkened at its edges.“I pray to God they never get rid of this history,” Brown said. “We as a Black race went through so much, and they’re trying to erase that.”The lynching memorial has two sister sites in Montgomery—the Legacy Museum, which traces the history of Black oppression in America from slavery to Jim Crow to mass incarceration, and Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, a 17-acre site that uses both contemporary sculptures and original artifacts to illuminate the lives and experiences of enslaved people. All three were created by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit legal organization founded in 1989 that has expanded into narrative and public-history work over the past decade and a half under the leadership of its founder and executive director, Bryan Stevenson.Stevenson began his career as a public-interest lawyer, and went on to argue in front of the Supreme Court on five occasions, winning favorable judgments in all but one. He successfully argued, for example, against mandatory life sentences without parole for children, and for incarcerated people with dementia to be protected, in some cases, from execution. But he has said that as time passed, he came to understand that his legal work would not be enough on its own to effect meaningful criminal-justice reform. The American public, he felt, needed a deeper understanding of how the realities of the country’s history shaped the present-day system.The Legacy Museum, which opened almost eight years ago, is perhaps the closest thing America has to a national slavery museum. Crucially, however, it is completely…

The Snow Monsters of Mount Zao

‘Looksmaxxing’ Reveals the Depth of the Crisis Facing Young Men

Minnesota Had Its Birmingham Moment

Among those who defend the behavior of ICE in the shooting of Renee Nicole Good, one argument goes like this: Activists have been recklessly trying to obstruct these agents as they carry out their work, all for the sake of getting a viral moment that makes the officers look like thugs. These ICE defenders are not wrong, but what they see as annoyance and endangerment seems more like a deliberate strategy with a long history—a successful one. The unarmed, nonviolent citizens who have been following ICE agents, blowing whistles to alert people to their presence, even heckling and mocking them, are not just trying to impede their work. They are aiming, as well, to illustrate a contrast, evoke a reaction that will reveal a moral truth, and tell a story they can capture on their phone: on one side, an aggressive, violent, extrajudicial (and masked) paramilitary group exercising brute force against anyone who gets in their way, and on the other, people who are simply attempting to be decent neighbors. Good and her fellow “rapid responders” achieved this contrast—at the cost of her life.Some people might think this is unfair, that ICE agents are just trying to do their job of finding and deporting undocumented people, and that the activists are to blame for provoking the violence. But this is not the way the activists see it, and after Good’s killing, it’s not the way the majority of the country sees it either. A CNN poll conducted after the shooting found that 51 percent of Americans believe that “ICE enforcement actions were making cities less safe rather than safer.” And the number of people who feel that Trump’s immigration-enforcement efforts go too far has grown, increasing from 45 percent last February to 52 percent in the new poll. The change is incremental, but for those who have been opposed to ICE all along, it is steady progress. What the neighborhood-watch groups and activists are doing in Minneapolis seems to be working, and their tactics are worth recognizing today in particular as Americans reflect on the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr.The civil-rights movement was built on creating and exploiting (in the best sense) such moments of moral witness, images of contrast. And King was the most prominent promoter of this approach. Sitting in a jail in Birmingham, Alabama, in April 1963, where he was detained for eight days, he composed one of his most famous pieces of writing: a letter to a group of clergymen who were advocating a more moderate approach to activism. (The Atlantic published it in the August 1963 issue under the headline “The Negro Is Your Brother.”) King was in the city as part of a campaign, called Project C (for confrontation), to break segregation in a place where it was as settled as sedimentary rock. The movement organizers had planned a series of rolling marches and sit-ins everywhere from the local Woolworth’s to the public library. The cartoonishly racist commissioner of public safety known as Bull Connor had tried to shut it all down by obtaining an injunction against protesting—which is how King ended up behind bars. [Read: The unspeakable, enabled]Persuading the local authorities to come to the table and loosen racial restrictions demanded the “creation of tension,” King wrote in his letter. The movement would have to provoke “a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation.” He was even prepared to accept the label of “extremist,” he wrote. “The question is not whether we will be extremist, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate, or will we be extremists for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice, or will we be extremists for the cause of justice?”The confrontations in Birmingham were being staged for an audience, just as the many people who filmed the moment when Good was shot—including the ICE officer, who sought to tell his own story—were recording for an audience. King knew that he couldn’t easily…

How to Understand Trump’s Obsession With Greenland

Kevin Harlan’s Radio Call Of Caleb Williams Miracle TD vs Rams Was Wild (AUDIO)

Will Anderson Jr. Told CJ Stroud He’s “Still The Best QB In NFL” After Horrendous Performance vs Patriots (VIDEO)